MAHLER

Program Notes

Return to Home Page |

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A Minor (“Tragic”)

Gustav Mahler’s Sixth Symphony is structurally his most conservative: it begins and ends in the same key (A minor) and has a traditional four-movement form. In terms of expression, however, it is not conservative at all. It stretches the capabilities of Mahler’s largest orchestra with relentless marches, angular melodies, and adventurous harmonies. Contrary to the 19th century ideal of blending textures, Mahler was drawn to the possibilities of dynamic opposition in older contrapuntal forms. He drew inspiration from the sounds he heard walking in the forest near a carnival:

That is polyphony, and that is where I got it from!...The themes must come from entirely different directions just like this, and be as different in rhythm and melody. [T]he artist...organizes and combines everything to a unified entirety.

Though the composer was ambivalent about attributing programmatic aspects to his works, he informally titled the Sixth the “Tragic” Symphony without providing a detailed program; various interpretations of the work’s meaning have derived from anecdotal conversations between Mahler and his friends and his wife Alma. The Sixth has been called both absolute music and a portrayal of the fall of a Hero, Mankind, or Mahler himself.

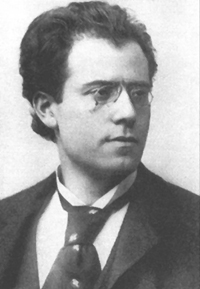

Mahler was born to a German-speaking, Austrian Jewish family in Bohemia in 1860. As a youth, he took piano lessons and absorbed the sounds of parades and fanfares from a nearby military base. After studying harmony and composition in Vienna, he eventually established himself as a conductor in Prague, Leipzig, Budapest, and Hamburg before taking over the prestigious Vienna Opera in 1897. His stewardship marked a pinnacle for the company, though Mahler was dogged by controversy over his exacting musical standards and difficult temperament. Furthermore, despite his conversion from Judaism to Catholicism before accepting the appointment, Mahler faced numerous anti-Semitic attacks from the musical establishment. The conducting post required so much of his time that composing was limited to summers.

Although the years immediately preceding the composition of the Sixth Symphony were turbulent for Mahler, it was during this time that he gained widespread recognition as a composer. In 1901 he was besieged with numerous problems at the Opera in addition to a health scare, but Mahler recovered from both well enough to begin one of the happiest periods of his life. His Second, Third, and Fourth Symphonies were accepted positively by increasingly broad audiences, and he completed his optimistic Fifth Symphony. In 1902, he married Alma Schindler, who was 20 years his junior; two daughters followed in two years. He completed Kindertotenlieder, a work whose meditation on the deaths of children was a sharp distinction to the optimistic Fifth Symphony and his happy family life. In this period he also began writing his only symphony that does not end in triumph or positive transformation—the Sixth. Its nickname “Tragic” fit it well. (Bruno Walter attributed the name to Mahler, though Mahler had disdained nicknames, and it appeared only once on a concert program in his lifetime.) Wilhelm Furtwängler called the Sixth the “first nihilist piece in the history of music.” Why was Mahler preoccupied with death at such a happy time? Alma believed he was fearful of the future, and she observed that “not one of his works came as directly from his innermost heart” as the Sixth Symphony.

I. The Allegro energico, ma non troppo is in sonata form with exposition repeat. From a programmatic point of view, the Allegro introduces a Hero marching vigorously across the stage. His progress is abruptly halted by the first appearance of the motif that Paul Bekker calls “an unchangeable verdict of Fate”: a martial timpani rhythm pounded under a chord in the trumpets and oboes that shifts from major to minor. This is followed by a woodwind chorale that Norman Del Mar calls “calm faith even under the severest adversity.” Next comes a sweeping romantic theme, which Alma (not the most consistent source) maintained was a portrait of her. After the repeat, a four-part development treats these themes ingeniously. In the expansive “Alpine” section, cowbells, celesta, woodwinds, and strings create what Mahler called “the loneliness of being far away from the world...a sound of nature, echoing from a great distance...” The return of the march jolts the Hero back to reality. A complex recapitulation reintroduces the Fate motif, which is brushed aside by the chorale in quick tempo. Constantin Floros calls the coda a “second development” where quiet march motifs in the trombones are shouted down by a sudden fortissimo that “chase[s] away thoughts of death.” The march then sets off on an exuberant and somewhat desperate rush with the “Alma” motif to the end.

II. The demonic Scherzo is composed of three main (“A”) sections, two intervening trios (“B”), and a coda (“C”). The opening resembles the initial march of the first movement but in triple time and with timpani accents “misplaced” to the third beat. That timpani motif introduces each “A” section, a danse macabre with grotesque woodwind trills, col legno strings (played with the wood of the bow), and a rattling skeleton of a xylophone. Underneath the danse, a swelling triplet moans in the bassoons, horns, and trumpets, later growling in the tuba and trombones, before roaring triumphantly in the high trombones. In the last “A,” the Fate motif returns ominously as sustained chords in the woodwinds and horns.

The calmer trio “B” sections are introduced by spiky woodwind solos and written with oddly shifting rhythms, tempos, and accents. Alma’s claim that they represent her “two...children [playing in] the sand” is contradicted by the fact that the movement was composed when her eldest daughter was but a year old and her youngest was unborn.

The coda is preceded by a grotesque passage with horns writhing downward in thirds and grace notes before landing with a soft thud and joined by the tuba. The insistent solo violin introduces the coda, where snide solo woodwinds mock the Hero before retreating into the distance. Timpani close with the final words.

III. The Andante moderato occupies another world with its ardent lyricism and remote tonality of E flat major. Fear seems absent, though uneasiness simmers beneath the surface. The first section introduces a seemingly simple but harmonically unusual gentle melody atop a rocking lullaby accompaniment, countered by a plaintive English horn statement with downward lamenting eighth notes. A bright minor third in the flutes and strings begins the next section, where the earlier motifs develop into a complex, tortuous texture; the cowbells are reintroduced in an early climax with hunting horns. The tumult subsides and the lullaby returns, allowing a moment of repose and reflection, before a surging climax soars in ecstatic anxiety, only to die away, its passion spent.

IV. The huge, half-hour Finale: Sostenuto–Allegro moderato–Allegro energico is an extended sonata form filled with elements from earlier movements. A geyser-like gushing in the strings opens the introductory Sostenuto. There follows what Floros calls “almost impressionistic technique of suggestion...[as] the music operates on two...different levels...unreal, dreamlike, far removed; the other is in the foreground and real.” He is referring to an eerie pastiche of the earlier Fate themes: a glowering tuba and contrabassoon, mysterious church bells, a calling forth by the horn, and a long, darkly orchestrated dirge. The Allegro moderato begins with striving motifs in the brass and high spirits in the horn, winds, and strings. Things come to a near halt with a return of the “geyser” (development). Tuba, cowbells, and church bells brew a creepy sense of danger; the atmosphere darkens with ominous brass fanfare motifs. The Hero is struck down by a hammer crashing to earth (second part of development), what Mahler calls “brief and mighty…dull in resonance and with a non-metallic character (like the fall of an axe).” The brass rage, and troops are driven with whipping sounds to quick-march, before a hopeful calm. The hammer falls again (fourth part of development). More chaos. The geyser gushes (recapitulation), Fate sounds, and the horns intone a lament with the tuba and bells as if gazing over a battlefield. The opening material, including the cowbells, reappears, now with heavy resignation. The oboe sighs but, in one of many changes of character, picks up the tempo in mid-statement as the Hero recovers. After a last major chorale in the brass, the Hero sallies forth to fierce battle. At times, he seems about to triumph, but after the gong and geyser erupt one last time (coda), he is struck down for good by Fate. Trombones and horns sing a canonic eulogy only to be stamped out once and for all by Fate, now entirely in the minor.

The Sixth is Mahler’s most revised and controversial symphony, with many issues open to question. The most controversial is the order of the inner movements. The score Mahler used to rehearse the premiere placed the Scherzo second and the Andante third (S-A). One of many changes he made in those rehearsals was to reverse that order (A-S). He then demanded a second edition from the publisher with errata slips inserted in unsold copies of the first. All performances up to 1919, including the three Mahler conducted and one by Willem Mengelberg, were A-S.

Mengelberg was preparing his second performance in 1919 when he came upon a first edition score, probably without an errata sheet. Surprised by its S-A order, he telegrammed Alma whose response, “First Scherzo, then Andante,” induced him to employ S-A for that concert and another in 1920, the only S-A performances for decades. In 1963, Erwin Ratz prepared a Critical Edition score for the International Gustav Mahler Society. He reinstated S-A because Mahler composed the work that way, and Ratz believed the composer had changed his mind again after the premiere. Ratz provided no evidence on the latter point, but most conductors fell into line. These “Mahler’s intention” arguments were joined by musical issues like the alleged awkwardness of A-S’s going from the A minor of the Allegro to the E-flat major of the Andante, overall tonality, etc. Some believe the Scherzo sounds too much like the Allegro to follow it, and that the Andante’s lyricism comes too late. Others think the Allegro and Scherzo belong together and that the Andante is an ideal lead-in to the Finale.

In 1998, Jerry Bruck argued that Ratz had no evidence endorsing S-A other than Mahler’s first score, adding that Alma’s telegrammed position was contradicted in her memoirs and by other oddities and inconsistencies. Bruck’s arguments convinced even Reinhold Kubik, whose 1998 revision of the Critical Edition had retained Ratz’s S-A order. Kubik changed the International Gustav Mahler Society’s position to A-S in 2004, and asked that publisher C.F. Peters to reflect that change in its score, which they did in 2010. Conductors are now split, tacitly endorsing Benjamin Zander’s assertion that there are two Sixth Symphonies, a composer’s (S-A) and a conductor’s (A-S).

Another issue concerns the hammer blows. Bekker saw them as “a supernatural, crushing effect that mankind can no longer fight against.” Mahler started with five but cut two for musical reasons (each strike marks a vital structural point) before the premiere. After the premiere, he eliminated the one striking down the Hero at the final coda. Alma claimed he did it in a failed attempt to avoid the Hero’s fate and cited three 1907 setbacks: his elder daughter’s death from diphtheria, his resignation from the Vienna Opera, and the diagnosis of the heart disease that killed him four years later. Her detractors claim Mahler removed it for the same musical reasons that he eliminated the first two blows. The work is now often performed with these two hammer blows, though some conductors retain the third.

That the Sixth was Mahler’s last symphony to gain acceptance did not surprise the composer, who said to Mengelberg, “My Sixth seems to be yet another hard nut, one that our critics’ feeble little teeth cannot crack.” To Richard Specht, he added, “[It] will be asking riddles that can be solved only by a generation that has received and digested my first five.”

Indeed, Richard Strauss was puzzled, but Arnold Schoenberg adored it. Alban Berg called it “the only Sixth, despite the Pastorale.” Perhaps the answer to those riddles is the symphony’s audacity.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra, Lowell House Opera, Dudley House Orchestra, and Bay Colony Brass (where he is also the Operations/Personnel Manager), and is a local freelancer. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener's Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony.

Return to Home Page

|