BERNSTEIN & HINDEMITH

Notes on the composer and the pieces

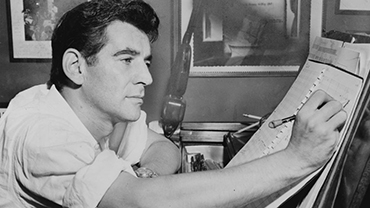

Leonard Bernstein

Symphony No. 1 “Jeremiah”

Paul Hindemith

Symphony Mathis der Maler

Return to Home Page |

Leonard Bernstein: Symphony No. 1 “Jeremiah”

American composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) attended Harvard University, studying with Walter Piston, and the Curtis Institute of Music, where he studied with Isabella Vengerova (Piano), Fritz Reiner (conducting), and Randall Thompson (orchestration). At the Tanglewood Institute (1940), he studied conducting with Serge Koussevitzky and became Koussevitsky’s assistant. In 1943, a few months after becoming Assistant Conductor of the New York Philharmonic (NYP), the 25-year-old Bernstein was a sensational substitute for Bruno Walter in a nationally broadcast NYP concert. Two years later, he took over the New York City Symphony Orchestra, and in 1951 the orchestral and conducting departments at Tanglewood. As Music Director of the New York Philharmonic (1958-1969), his recordings and the Young People’s Concerts helped make him the American face of classical music. Bernstein promoted American composers—including Aaron Copland, William Schuman, Roy Harris, and Charles Ives—helped start the Gustav Mahler wave, and revived interest in Haydn with a series of recordings. He conducted the “Berlin Celebration Concerts” in Germany as the Berlin Wall was taken down. His telecast of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 with the NYPO after John Kennedy’s assassination was the first of a Mahler symphony. For Robert Kennedy’s funeral, he led the NYP in the Adagietto from Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 at St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Although he made his reputation as a conductor, Bernstein claimed his true love was composing. For his 70th birthday, Lauren Bacall sang a hilarious song by Stephen Sondheim, “The Saga of Lenny,” which parodied Bernstein’s inability to decide what talent to focus on and summed up his lifelong plight. (The song was a takeoff on a Kurt Weill song, “The Saga of Jenny.”) Bernstein the composer may be best remembered for West Side Story, Chichester Psalms, Candide, the music for On the Waterfront, and Jeremiah Symphony, also known as Symphony No. 1.

Jeremiah Symphony grew out of a “Hebrew song” Bernstein wrote for soprano and piano in 1939 to a text from the Book of Lamentations about the destruction of Jerusalem. Nothing came of it until 1942 when he competed for the Paderewski Prize for American Composers, sponsored by the New England Conservatory. His Jeremiah Symphony, with “Hebrew song,” adapted for mezzo-soprano as the last movement, finished second to Gardner Read’s Symphony No. 2. Pittsburgh Symphony conductor Fritz Reiner loved Jeremiah, and allowed Bernstein to conduct its 1944 premiere with Pittsburgh and mezzo-soprano Jennie Tourel (who sang on its first and best recording, with the NYPO). Jeremiah was a breakthrough, the first of several pieces that were, in Bernstein’s words, “about the struggle...born of the crisis of our century, a crisis of faith.”

Bernstein associate Jack Gottlieb wrote that the symphony was drawn from a two-part motto in the opening: the “amen” of the Amidah for festival morning and the amen [from the 4/4] to the K’rovoh. This motto runs through the first movement and appears in the two others. There are other influences from Hebrew liturgy as well, especially in “Lamentation.” The symphony can be viewed as an expanded sonata form, with the three movements taking the roles of exposition, development, and recapitulation.

Bernstein wrote that “‘Prophecy’...aims only to parallel in feeling the intensity of the prophet’s pleas with his people.” The motto winds its way through the orchestra punctuated with angry brass chords. In one touching moment, a sad trumpet looks over the future wreckage. The mood lightens in a lyrical passage topped by an eerie piccolo. As the music gathers strength, the angry accents return. Trumpets repeat their call, and the movement ends quietly on a sustained note in the low strings.

“Profanation” takes the motto on a bacchanale that gives “a general sense of the destruction and chaos brought on by the pagan corruption within the priesthood and the people.” Bernstein confessed to “a deep suspicion that every work I write, for whatever medium, is really theater music in some way.” That is especially true in this movement. Stravinsky is an influence, but this is the Bernstein of Broadway. Kenneth Lafave wrote that its wildly erratic rhythm and meter changes reflect the Hebrew language. He adds that Bernstein told Humphrey Burton that he “sped up and ‘rhythmicized’ the tune in the “central idea of this movement” from what he sang at his Bar Mitzvah. Soon after the second appearance of an oddly breezy string melody, the horns sound forth with the motto, setting off a rush to a riotous conclusion.

“‘Lamentation’ [is]...the cry of Jeremiah, as he mourns his beloved Jerusalem, ruined, pillaged, and dishonored after his desperate efforts to save it.” Its thematic ideas are based on the motto. The first is a long Hebrew recitative sung by the mezzo-soprano over sustained notes from changing orchestra sections. A sad, lyrical flute solo begins the next. The violas introduce the third, a halting rhythmic figure, before the singer reenters. The music treats all three, with the halting idea becoming dominant by transforming into a funeral march. After a full orchestral climax, the symphony ends in submission and sadness.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra, Lowell House Opera, and Bay Colony Brass (where he is the Operations/Personnel Manager). He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. His latest fiction collection, The Audition and Other Stories, includes a novella about a trombonist preparing for and taking a major orchestra audition (English Hill Press, 2013).

Return to Home Page

> BUY TICKETS

|