RACHMANINOFF

Notes on the composer and the pieces

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Symphony No. 2

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini

Return to Home Page |

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Sergei Rachmaninoff was born in Novgorod, Russia in 1873. His family were landed aristocrats until his father’s debts forced them to move to St. Petersburg, where nine-year old Sergei enrolled at the conservatory. After diphtheria took his sister, and financial stresses separated his parents, the boy moved to Moscow in 1885, where his teacher, Nikolai Zverev, took him into his home, instilled some discipline, and introduced him to several famous composers who visited there. Among them was Pyotr Tchaikovsky, who would later call Anton Arensky, Alexander Glazunov, and especially Rachmaninoff the most promising Russian composers.

In 1888, Rachmaninoff enrolled in the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied with Alexander Siloti, one of Zverev’s pupils, as well as with Arensky and Sergei Taneyev, who would become a revered mentor. Rachmaninoff graduated as a pianist in 1891 and in composition in 1892. A few of his student works are still performed, including Prince Rostislav, Aleko, Prelude in C-Sharp Minor, and Piano Concerto No. 1.

Rachmaninoff’s career proceeded smoothly until the 1897 premiere of his Symphony No. 1, which was mangled in a performance conducted by the in-over-his-head and possibly inebriated Glazunov. Composer and critic Cesar Cui called the work an attempt to describe the seven plagues of Egypt by a graduate of a “conservatory from Hell.” Rachmaninoff’s confidence was so shaken by the symphony’s failure that he disowned it and reportedly refused to take the score with him when he left Russia for good in 1917. (The orchestra parts survived. The reassembled score of what actually is a great work was first played in 1945.)

That debacle left Rachmaninoff blocked as a composer for three years, but he thrived as a pianist and as a conductor, starting with a successful stint with the Mamontov Opera Company. His creative block distressed him, however, and in 1900, he entered hypnosis therapy with Dr. Nikolai Dahl that he believed solved his problem, though a subsequent trip to Italy probably helped. The first sign of recovery was the start of his Francesca da Rimini (1905), but the real breakthrough was his Piano Concerto No. 2 (1901, dedicated to Dr. Dahl). In 1902, he thought of writing a second symphony, possibly to fulfill a promise to Siloti, but before anything came of that, he produced the Cello Sonata, the first set of Piano Preludes (1903), and The Miserly Knight (1904).

The symphony lingered in the background, but the problem was finding time to work on it, especially since he began conducting at the Bolshoi in 1904 and was busy as a pianist. The political turmoil that was starting up in Russia supplied its own disruptions, with “Bloody Sunday” occurring in January 1906.

Finally, in November 1906, Rachmaninoff cancelled all his obligations and moved his family to Dresden, Germany, a restful city filled with pleasant memories of performances of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger and Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony, and located near Leipzig, where Artur Nikisch, highly respected by the composer, conducted at the Gewandhaus. During his three years in Dresden, he produced Piano Sonata No. 1, Piano Concerto No. 3, Isle of the Dead, and Symphony No. 2.

In 1909, he set off on an American tour, where he played his new concerto under Gustav Mahler in New York. While in the U.S., he turned down several job offers, including the music directorship of the Boston Symphony.

Rachmaninoff’s return to Russia in 1910 began a busy but also difficult period for the composer. He assumed the directorship of the Moscow Philharmonic Society orchestra (until 1914), performed as a pianist, and went on a few tours. At the same time, the traditionalist composer had to share the stage with innovative figures like Igor Stravinsky, Alexander Scriabin, and Serge Koussevitzky, as well as endure the deaths of his father, Scriabin, and Taneyev.

Meanwhile, the political situation exploded into the Russian Revolution in 1917. Peasants seized Ivanovka, and the bourgeois Rachmaninoff family felt threatened enough to flee their country in November, never to return. Works from his final years in Russia included a second set of piano preludes, songs, The Bells and Piano Sonata No. 2 (both 1913), All-Night Vigil (1915), and a second set of Etudes-Tableaux (1917), the last work he wrote in his native land.

The Rachmaninoffs’ escape was facilitated by an invitation for concerts in Scandinavia. Even so, the family arrived in Sweden with little money and few possessions, but Rachmaninoff obtained enough work as conductor and pianist to rebuild his finances.

In November 1918, the family set sail for America. Rachmaninoff’s pen was still for eight years, while he led a whirlwind life mostly as a pianist, but also as a conductor and recording artist back and forth in North America and Europe. Finally, he produced Piano Concerto No. 4 (1927, rev. 1941) and Three Russian Songs (1929). The concerto’s mostly unenthusiastic reception awoke memories of his failed First Symphony and stalled his composing again, but in 1931, he completed Variations on a Theme by Corelli (1931) for piano, his first major foray into the variations form.

In 1932, Rachmaninoff built a villa near Lucerne. That is where he took the “theme and variations” form a step further with Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini (1934). He played its successful premiere in Baltimore with the Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Leopold Stokowski. The Rhapsody’s success encouraged its composer to write two more major works: Symphony No. 3 (1936) and Symphonic Dances (1940). Sergei Rachmaninoff became an American citizen in 1940 and died in 1943, leaving behind the question as to what kind of composer he would have been had he remained in Russia. He certainly wrote less after he left, his style changed, and he was uncomfortable in the U.S. Late in life, he famously said that when he fled Russia, he “left behind the desire to compose. Losing my country I lost myself also...there remains no desire for self-expression.”

Symphony No. 2, op. 27, in E minor

Rachmaninoff hated the first draft of this work. “I don’t know how to write symphonies,” he wrote to a friend, “and…I have no real desire to write them.” (Until Tchaikovsky, the symphony was mainly a structured Germanic form based on development and changing harmonies, as opposed to the Russian use of folk melodies, more static harmony, blockier orchestration, etc.) He persisted, composing in Dresden and orchestrating in Ivanovka. He dedicated the finished product to Taneyev (to the displeasure of Nikisch) and conducted the premiere in St. Petersburg in 1908. The work’s success surprised its composer, and won him his second Glinka Prize in 1909. Even so, he did not write another symphony until 1935.

Symphony No. 2 follows the late Romantic Russian idea of the symphony, as represented by Alexander Borodin. Together with the even more romantic Piano Concerto No. 2, it symbolizes Rachmaninoff’s rejection of his failed First Symphony.

The Second Symphony is more muscular and expansive than the Second Piano Concerto. It is almost an hour long, and thickly and sumptuously scored. The string writing is often choral in style, and the four major orchestral sections are treated mainly as groups with few major solos. The work is long, melodic, and rhapsodic, with an undercurrent of unease periodically underlined by baleful brass chords and allusions to the Dies Irae (Figure 5), a signature motif with this composer. Rachmaninoff rarely produced such romanticism again.

In the 1930s, Rachmaninoff reluctantly agreed to about seventeen cuts in this symphony that conductors could choose from. It was performed with cuts for many years. When Andre Previn was touring in Leningrad, he was told that Rachmaninoff truly liked only “the small cut in the finale.” After reexamination of the score, Previn switched to performing the complete version. That is mostly the practice today, including this performance.

The symphony’s subtlety and complexity reward scrutiny. It is tied together by a seven-note motto, from which most of its subjects and themes are drawn. The motto is generally divided in two; ab is shared between the two. B is the more significant component except in the Allegro Molto.

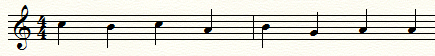

Figure 1. Motto

The motto’s stepwise character is typical of Russian Orthodox choral music. The motto is rarely played outright, but, as John Culshaw wrote, it “epitomizes the spirit of the symphony, and it moves through the work like a ghost, bringing forward new material and hovering in the background while the material is being stated and developed.” That motto and the practice of quoting from previous movements tie the work together.

Largo—Allegro Moderato is in sonata form with a long introduction. The motto’s linear quality is reflected in the character of this movement, where the motto is most prominent and recognizable. The symphony begins with the motto in the cellos and basses. The winds then play motto A, and the strings answer with B, creating a flowing introduction that ends with an English horn solo. The exposition begins with a syncopated pattern in the clarinets followed by Subject 1, a flowing line in the violins based mostly on B. The grander and sweeping Subject 2 begins in the clarinets and oboes.

Figure 2. Largo—Allegro Moderato: Subjects 1 & 2

Rhythms become more complex until the strings return to the syncopated clarinet passage that opened the exposition. The development begins with solos by the violin and treats Subject 1. After short dotted fanfare rhythms in the brass and quiet solos in the English horn and oboe, the recapitulation begins with flutes and clarinets leisurely playing Subject 2, the only idea treated in this section. After a brass call to arms, things quiet down with the clarinet and then bassoon leading the way. A nervous coda leads to an odd march that gives way to brass fanfares and an abrupt ending.

The structure of Allegro Molto is essentially ABA2CA3B2A4 (with A and B varying with each appearance). A is triggered by the horns into a headlong ride with skittering strings and driving brass. B is a lyrical interlude in the strings with sweeping horns and the march from the first movement. C is a vigorous string fugue interrupted twice by baleful brass chords, giving way finally to A3. A4 is spiced with the Dies Irae in the trumpets. Somber brass intoning an impression of the motif ends the movement.

Adagio opens with Melody 1, built on arpeggio sequences in the strings. The eighth-note figure at the beginning of the second and third measures lends a piquant spicing to this line. This quickly gives way to Melody 2 in the clarinet, the only long solo in the symphony. The strings take over with Melody 3 before falling back to Melody 1.

Figure 3. Adagio: Melodies 1, 2, & 3

After another baleful brass chord, things darken, and the music anxiously plays with the motto. After a climax, Melody 3 breaks out in the strings over timpani. After a long chord and a pause, the horn begins Melody 2, which travels through the orchestra in short solos. From there, the orchestra treats mainly Melodies 1 and 3. After an ethereal passage high in the violins, the movement comes to rest.

Finale (Allegro Vivace), written in sonata form, recalls material from all three movements and ties the symphony together. Theme 1 is a vigorous dance interrupted with a strange jaunty march interval until the opening material returns. After a short fanfare, the strings present a rhapsodic Theme 2. After that comes almost to a halt, the development begins with baleful brass chords. A powerful scale-filled passage leads to the recapitulation (Theme 1). After a long buildup and another fanfare, Theme 2 begins a lyrical coda. A long dissonant brass statement gives way to a triumphant ending.

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 34, for Piano and Orchestra

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini draws its theme from Niccolò Paganini’s Violin Caprice in A-Minor No. 24, the same one used in variations by Liszt, Schumann, and Brahms.

Figure 4. Rhapsody: Theme

Rachmaninoff often plays this theme against the Dies Irae figure. (John Culshaw believes there is a subtle “relationship” between Dies Irae and the second line of the Paganini theme.)

Figure 5. Dies Irae

The clever and inventive Rhapsody is played as one movement and ranges from sparkling, witty, and light-hearted to mysterious and dramatic. Its style, carried over from the Fourth Concerto, is more direct, spare and less Russian than Rachmaninoff’s earlier works. Most variations are short, so the piece moves quickly. Their beginnings and endings are easy to make out, though they become more complex and deeper as the work proceeds. The playing order is Introduction, Variation 1, Theme, Variations 2–24, and Coda. Variation 18, the most famous, is based on an inversion of the main theme. It is also the most romantic part of the work and the only one that looks back to the Rachmaninoff of the Second Symphony. The final music is unusually powerful, but Rachmaninoff turns that into a sly joke with a “throwaway” ending.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra, Lowell House Opera, and Bay Colony Brass (where he is the Operations/Personnel Manager). He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony. He is a regular reviewer for American Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback magazine. His latest fiction collection, The Audition and Other Stories, includes a novella about a trombonist preparing for and taking a major orchestra audition (English Hill Press, 2013).

Return to Home Page

> BUY TICKETS

|