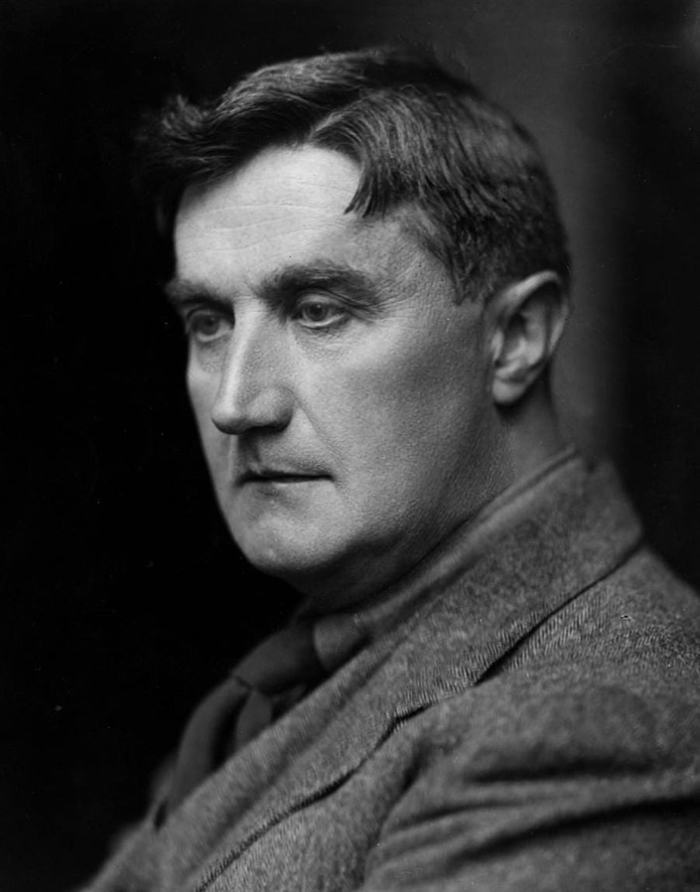

RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS

Notes on the composer and the pieces

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Symphony No. 4

Symphony No. 5

Return to Home Page |

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

The British symphony has not traveled well to the United States, partly because in the first half of the twentieth century, little English music was heard in Continental Europe, from where most conductors of American orchestras came. Nor did British maestros bring much of their music to American orchestras. British music is unique. Its modal, ethereal sound is imbued with England’s countryside and rocky coastline as well as its history, literature, and folklore, and it hides secrets that it begs the listener to discover. This music is emotional without sobbing; reserved, and yet noble. Much is drawn from English folk music, and it sings. The English have always sung, and their composers did not stop when they wrote symphonies.

Perhaps the greatest personification of this music is Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958, hereon VW), who broke from the Old World Romantic style of Edward Elgar to become one of the most important symphonists of the twentieth century. He wrote his first symphony in 1909, his last in 1957, and he was still evolving as a composer when he died.

VW was born in Down Ampney, Gloucestershire. Albert, his father, was a vicar. His mother, Margaret, was a descendant of the Wedgwood Pottery family and a grandniece of Charles Darwin. When Albert died a little more than two years after VW was born, Margaret moved her family to Surrey to live with her sister, Sophy, who gave VW his first music lessons. For her part, Margaret read aloud to him, sometimes venturing into Shakespeare, thereby planting the seeds for her son’s lifelong love for the Bard.

VW’s formal music schooling began in Rottingdean and continued at the Charterhouse School in Surrey. From there he attended the Royal College of Music (RCM) where his composition teacher, Hubert Parry, introduced him to Beethoven, helped him appreciate the grandeur of English choral music, and issued the memorable advice to “write choral music as befits an Englishman and a democrat.” At Trinity College, Cambridge, VW studied with Charles Wood and befriended philosopher Bertrand Russell and historian G. M. Trevelyan. In 1895, he returned to the RCM for lessons with Charles Stanford and began a fruitful friendship with composer Gustav Holst that lasted until Holst’s death in 1934. While in Berlin in 1897, he took composition lessons with Max Bruch. Ten years later, he studied orchestration with Maurice Ravel who taught him how to “orchestrate in points of color rather than in lines.” Two poets were also influences: Walt Whitman–whose texts VW set in A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1), Toward the Unknown Region, and Three Poems by Walt Whitman–and John Bunyan, whose Pilgrim’s Progress supplied the text for VW’s eponymous opera.

During the Great War, VW served on a British army ambulance crew and in the Royal Garrison Artillery where he was in charge of guns and horses. The resulting exposure to artillery damaged his hearing to the point that he was nearly deaf in his old age–one of several horrors inflicted on him by that war, including the loss of his friend, composer George Butterworth. After the war, he taught at the RCM and composed and conducted until the end of his life.

VW was married twice. His first wife, Adeline Fisher, was of more stolid temperament than her husband. After her brother died in the Great War, she began a lifetime of mourning and wore black for the rest of her life. When arthritis forced her into a wheelchair, she required considerable tending from her husband. Eventually, her lack of mobility forced them to abandon VW’s beloved London for rural Dorking where she could get around more easily. In 1938, the much younger poet and writer Ursula Wood (née Joan Ursula Penton Lock) was so overwhelmed by his Job that she vowed to meet its composer. Her success in meeting him led to an affair that progressed for years with Adeline’s knowledge. Two years after Adeline’s death in 1951, VW and Ursula married, and the couple moved to London. Ralph was 80; Ursula 42. She was a loving spouse who provided the text for a few VW pieces, served as a lifelong advocate of his music, and wrote an essential biography of her husband: R.V.W. A Biography of Ralph Vaughan Williams.

VW believed a composer must be true to his country and its people. He revered English Renaissance composers like Thomas Tallis, collected British folk songs, and applied both to his music. Although an agnostic (composer Anthony Payne called him a “religious agnostic”), he wrote a great deal for the English church, most notably the Mass in G minor. (“There is no reason why an atheist could not write a good Mass.”) He edited the 1906 edition of The English Hymnal adding several hymns of his own. As a composer, he was a visionary, often employing impressionism and/or pentatonic and modal scales. His orchestration produced warm clear-toned strings, pastel winds, and bold, broad brass. He wrote one great piece after another for all kinds of ensembles, venues, and levels of difficulty even during the Great War when he composed his first two symphonies, Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, Norfolk Rhapsody, The Lark Ascending, and the opera Hugh the Drover. After the war came seven more symphonies, four more operas (The Pilgrim’s Progress, Sir John in Love, The Poisoned Kiss, and Riders to the Sea), four concertos, many orchestra works (Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus, Partita for Double String Orchestra, Fantasia on “Greensleeves” [originally from the opera Sir John in Love], and others), and choral works (Sancta Civitas, Five Tudor Portraits, Dona Nobis Pacem, Hodie, and others). He did not care for “dancing on points,” but he wrote the ballet Job–a masque, he called it–after William Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job. VW’s film scores included 49th Parallel, Coastal Command, and Scott of the Antarctic—from which he adapted Sinfonia Antartica, his Symphony No. 7. He also wrote innumerable songs and a variety of chamber music.

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): Symphony No. 4 in F Minor

VW wrote Symphony No. 4 in F Minor between 1931 and 1935. Dedicated to Arnold Bax, it is his most violent work, and its pounding, grinding brass and shrieking woodwinds led many to think it reflected his rage over the Great War, the rise of Hitler, frustration over his home life, or that it was a self-portrait. The composer insisted it was not a “picture of anything external...it occurred to me like this...It is what I wanted to do at the time” adding that, “it never occurs to these people that a man might just want to write a piece of music.” After conducting a rehearsal of the piece, he told the orchestra, “I don’t know if I like it, but it’s what I meant.” That said, it is hard to listen to the Fourth without picturing a storm.

Allegro opens with a surging onslaught of two ideas that permeate the work: Theme A (E-Eb-F-E) and Theme B (a rising F-Bb-Eb-Gb). A string tune takes over before giving way to a running motif in the horns. This section treats this music with energy and power before slowing down to a tenuous quiet with atmospheric middle strings and bassoons sighing and violins whispering in the distance. The storm returns with a heavy skipping rhythm, the tempest rebuilds to the crunching opening figure, and the section repeats. After things settle down we gaze upon a stricken landscape.

Andante moderato opens with a frightened Theme B looking nervously about before giving way to a spooky string fugato over low-string pizzicato. Winds are curious but frightened, but the orchestra gathers strength until Theme B rises in the brass. After lonely wind soliloquies, the orchestra stirs powerfully with Theme B, fades, and the spooky string passage returns. After a quiet complex treatment of this material, the movement ends with a mournful flute.

Scherzo resembles a demonic game of tag first based on Theme B, interrupted by thrusts of Theme A. The complex game continues until a bumptious fugue based on Theme B rises through the brass and winds and then returns to parts of the movement’s opening. The fugue reappears in the brass and proceeds through a passage reminiscent of the eerie transition between the last two movements of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony directly into the...

Finale. After the opening, a folkish tune sets in over “oom-pah” (VW) low brass. Things get wild until the folkish section returns. After a look back to the uneasy peace of the slow movement, the furious opening music comes back. Chaos ensues. The piece seems about to end, but the trombones’ proclamation of Theme A sets off the Epilogue, which scrambles wildly until halted by grinding brass. A single angry chord slams the door.

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): Symphony No. 5 in D

VW wrote Symphony No. 5 in D between 1938 and 1943. It is related to The Pilgrim’s Progress, an opera VW started in his twenties but gave up on before completing it in 1951. Several of the opera’s ideas found their way into the Fifth, which was completed during World War II (VW called it his “war symphony”). Its serenity puzzled listeners even though his other “quiet” symphony, the Pastoral (Symphony No. 3), looked back to the Great War. Uneasiness and menace lurk beneath the surface of both symphonies.

The Fifth is dedicated to “Jean Sibelius without permission,” though there are only a few Sibelian elements. (A grateful Sibelius soon granted “permission.”) The work evolves through modal tonality to a glowing conclusion, and all four movements end quietly.

Preludio is built around a horn call and an answering figure in the violins. A searching modal melody sounds in the strings over a pizzicato bass, and eventually is worked into contemplative polyphony. The next section brightens and gives way to bustling strings darkened by stern dropping seconds and fragments from the earlier section before building to the first climax. The horns reintroduce their opening call, and earlier themes build to the main climax, which is an extended passage of exaltation and celebration countered by the dropping seconds. After the horns sound their opening call, the movement ends in uncertain peace.

Scherzo begins with awakening strings followed by wind solos and assorted figures, some devilish in tone. Behind all that is a trombone hemiola that suggests a train pulling out of a station, as well as a wry chorale-like melody that repeats through the orchestra in a variety of scoring. After the lively material returns, various motifs appear and become aggressive, particularly a march-like passage that ends up in the brass. After a lightweight moment for flute, bassoon, and strings, quiet string threads drift away to the end.

Romanza suggests a slow gathering for a prayer meeting. Its two basic elements are a short chorale introduced by the winds, an English horn solo drawn from The Pilgrim’s Progress, and a long exploratory string melody. The winds extemporize, and the chorale and string melody return in rapture, leading to a duet for oboe and English horn, followed by playful winds. The tone becomes harsh with muted trumpets, but the horn calms things with the opening theme, allowing a climax to ring forth in the brass. Like a signpost the chorale reappears in the brass, countered by broad strings, and the long calming string melody returns with power and assurance. A long lyrical theme is followed by a ruminative violin dialogue with the rest of the orchestra, and earlier ideas return. The ending is sublime.

The subject of Passacaglia begins in the cellos and is repeated with variations. The orchestra builds to a brilliant climax that gives way to a blazing D Major chord in the trombones, like sunshine through a window, recalling the ending of Brahms’s Second Symphony. The opening returns and reaches another climax before settling back. After the horns sound their opening call, strings, woodwinds, and horns wander through the movement’s opening material as if looking back with fondness and regret before coming to rest.

Ralph Vaughan Williams was seventy-one when he finished the Fifth Symphony. Many thought it was his farewell, but he composed for fifteen more years. He died on August 26, 1958, the night before he was to supervise the first recording of his Ninth Symphony under conductor Adrian Boult. His wife kept the spirit of his music alive after his death. She devoted much of her own life to supporting his music until she died in 2007.

—Roger Hecht

Roger Hecht plays trombone in the Mercury Orchestra and Bay Colony Brass (where he is the Operations/Personnel Manager). He is a former member of the Syracuse Symphony, Lake George Opera, New Bedford Symphony, and Cape Ann Symphony, as well as trombonist and orchestra manager of Lowell House Opera, Commonwealth Opera, and MetroWest Opera. He is a regular reviewer forAmerican Record Guide, contributed to Classical Music: Listener’s Companion, and has written articles on music for the Elgar Society Journal and Positive Feedback Magazine. His fiction collection, The Audition and Other Stories, includes a novella about a trombonist preparing for and taking a major orchestra audition (English Hill Press, 2013).

Return to Home Page

|